(MintPress) – Exactly 150 years after the largest government-sponsored mass execution in U.S. history, a cross-state march from South Dakota to Minnesota is taking place in the honor of those who fell victim, with the intent not only of remembering the past, but highlighting the lessons learned and a healing process so desperately craved by those whose ancestors fell before them.

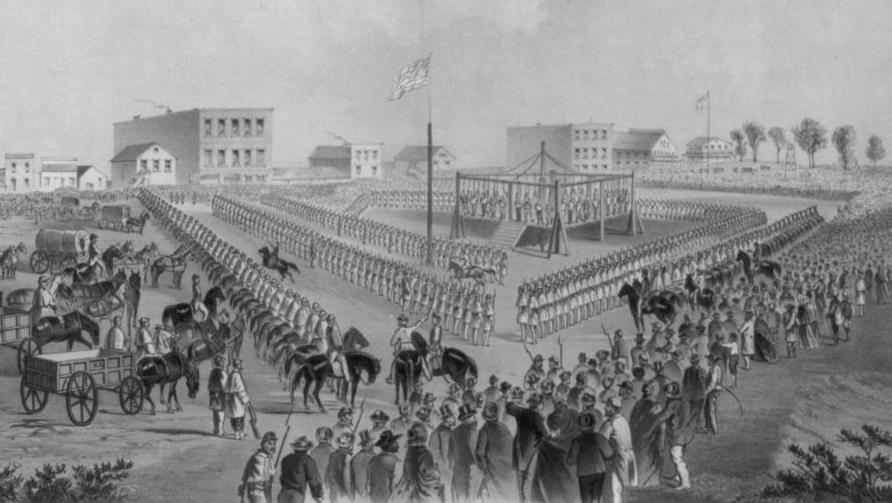

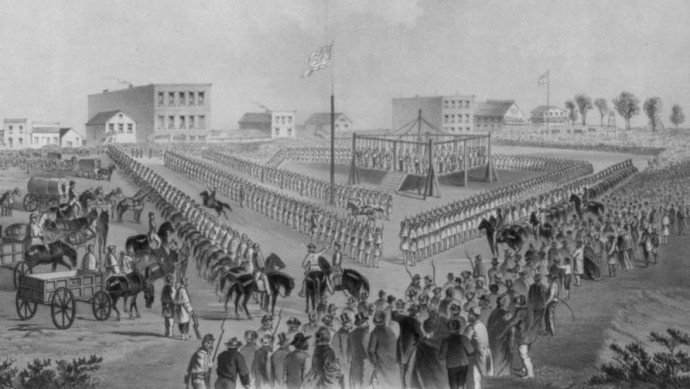

On Dec. 26, 1862, the order was given by then-President Abraham Lincoln to hang 38 Native Americans in what is now known as Mankato, Minn. Their crimes stemmed from a war between the indigenous population and European settlers, in which Native Americans rebelled in the face of failed treaties.

“Delayed and skipped payments drove the Dakota to increasing desperation with each passing year,” according to the U.S. Dakota Conflict of 1862: A Self Guided Tour. “Through deceptive business practices, unscrupulous traders and government agents took much of what the Indians did have. Poverty, starvation and general suffering led to unrest that in 1862 culminated in the U.S.-Dakota conflict …”

The war, which began in August 1862, started with an attack on a European settlement, resulting in the death of five Europeans. This sparked the war, as fighting escalated, culminating in an undocumented number of deaths among Native Americans and 400 among Europeans.

The war ended with the hangings of Dec. 26, 1862.

Following the war, which ended with the Mankato hangings, Native Americans were driven from the land by the government. Some left on foot, others by government-sponsored transportation, which eventually led them to a Native American prison in South Dakota.

Dakota ride

Native Americans and supporters of the movement began their journey two weeks ago in Lower Brule, S.D., where they departed on horseback, destination Mankato. The starting point for those making the journey is symbolic, not only because it is their home, but because it was there where their ancestors were shipped following their banishment from Minnesota.

While the 150th anniversary was the inspiration for the ride, the annual Dec. 26 gathering on the site of the hangings takes on extra meaning this year, as a new memorial engraved with the names of those who were executed is being unveiled.

It’s a somber time for everyone, but according to Native Americans making the pilgrimage, it’s about healing a community inflicted with drug abuse and alcoholism. Cheyenne River Reservation is located in one of the poorest counties in the nation. Suicide has plagued the community, with 17 youth taking their lives in 2002 and 2003 alone.

“We can’t blame the wasichus anymore. We’re doing it to ourselves. We’re selling drugs. We’re killing our own people. That’s what this ride is about, is healing,” Native American spiritual leader Jim Miller said in “Dakota 38,” a documentary of the yearly ride.

Miller is considered the leader of the Dakota ride, as he was the first to propose a horseback journey to Mankato, Minn., based on a dream he encountered in 2005. The Vietnam veteran did not know at the time of the Mankato hangings, yet his vision was the very scene that occurred 150 years ago — 38 men were hanged simultaneously.

“When you have dreams, you know when they come from the creator … As any recovered alcoholic, I made believe that I didn’t get it. I tried to put it out of my mind, yet it’s one of those dreams that others you night and day,” he said.

The film not only documents the journey that takes place today, but follows the historical path that led to the Dakota hangings. One newspaper clipping from the St. Paul Pioneer Press depicts the attitude between Native Americans and Europeans during that time. Dated Sept. 23, 1983, the write-up is titled, “Good News for Indian Hunters.”

“The Indian-hunting trade, if the game be at all plenty, is likely to prove a profitable investment, during the present fall and winter to our hunters and scouts in the Big Woods, the Commander-in-Chief, by the General Order No. 60 having increased the bounty for each top-know of a ‘bloody heathen,’ to $200. There is likely to be a considerable competition in the trade, and the best shots will carry off the most prizes,” the newspaper article states.

Reflecting on the past, those who take the journey are aware of the differences that still persist today between Native Americans and European-Americans, recognizing there still exists a need for the two communities of people to come together in peace, to forge relationships that transcends ancestral racism and bias.

Lessons learned, history unraveled

While the intent is certainly to unite and endure the healing process through the ride, a major component of the cross-state trek is also education. Many Minnesotans are unaware that the largest government-sponsored execution took place in that very state.

Chris Mato Nunpa, retired professor of Dakota studies, addressed this issue in “Dakota 38,” claiming that at some point, the historical events of Minnesota and the treatment toward Native Americans will be widely recognized. As Nunpa points out, 3 billion acres of land were taken in land grabs by European settlers, more than 400 treaties were violated — and more than 90 percent of an entire Native American community in the continental U.S. was wiped out over four decades.

“What happened?” he asks.

The answer to that question is something Native Americans hope is discussed in an honest manner. The truth, while not pleasant, is not met by anger among those who join the trek to Mankato. They feel anger, hurt and pain, but the intent is not to get even — it is to heal.

To commemorate the event, the Blue Earth Historical Society hosted monthly series through the year celebrating the Dakota people. Itinerary for the series included an introduction to traditional poetry, pow wow etiquette, reconciliation and various other forms of expression and artistic creation.

On Wednesday, the day of the 150-year commemoration, the Mankato Free Press published photos of the commemoration and those who made the journey from South Dakota. Hundreds gathered in what is now known as Reconciliation Park, taking those of European and Native American descent one step closer in the healing process toward peace.

“Today, being here to witness a great gathering, we have peace in our hearts — a new beginning of healing,” Dakota/Lakota leader Looking Horse told the crowd, according to the newspaper.