It’s a question that tests the limits of free speech and has once again resurfaced after marijuana legalization ads were plastered on city buses in places such as Portland, ME, this fall, since the city had a ballot measure to legalize recreational use of marijuana.

Critics argue the ads should not be allowed in public since they promote the use of what they consider a dangerous drug, which will lead to more drug abuse among minors. But proponents said the ads are a way to educate the public and dispel myths about the drug’s effects.

Although marijuana is illegal to advertise in some places because it is illegal federally, several federal judges have ruled that an advertising ban on substances, including marijuana, is a First Amendment violation, and that “any violation of the right to free speech is an irreparable injury.”

John Nicolazzo of the New York-based Medical Cannabis Network said that because marijuana marketing is so new, federal threats still exist against those who publish any pro-legalization materials, and there is more scrutiny for marijuana ads than those who advertise alcohol and tobacco products.

For example, in Colorado, the Amendment 64 Implementation Task Force recommended to the state legislature this past March to “prohibit all mass-market campaigns that have a high likelihood of reaching minors (billboards, television, radio, direct mail, etc.),” and would only allow pro-legalization advertisements in “adult-oriented newspapers and magazines.”

But the restriction directly conflicts with Article II, Section 10 of the state’s Constitution, which says “no law shall be passed impairing the freedom of speech” and “every person shall be free to speak, write or publish whatever he will on any subject, being responsible for all abuse of that liberty.”

“Our industry has been under constant scrutiny, and advertising is a big part of that,” Nicolazzo said. “It does kind of hinder us from going mainstream, to where we want to be.

“What’s the difference between advertising for marijuana, or when you go to the gas station and they have sign for $1-off cigarettes? At nightclubs, they’re handing out shots. When you try to compare alcohol and tobacco, there’s a very thin line.”

Balancing the interests of children with drug policy reform

Kevin Sabet is the director of the University of Florida Drug Policy Institute and a former adviser on drug issues to President Barack Obama and Presidents George W. Bush and Bill Clinton. He said he was concerned that widespread use of advertisements that endorsed the use of marijuana may send a message to kids that marijuana is safe.

“We’re witnessing the birth of Big Marijuana,” Sabet said, adding that the industry is using similar tactics that helped advance the tobacco industry: “It’s the advertising. It’s the billboards. It’s the vending machines. It’s the lobbying groups, all the things that Big Tobacco has mastered for 80 years.”

But Gregory Jordan, the general manager of the transit district that ran the ads, said “We’re allowing this message because it’s political speech. It’s designed to help change a law.

“It’s not the promotion of a commercial product. … We don’t have a position on the content of the advertising, just that it’s a political message and by its very nature it’s protected by the First Amendment.”

Jordan has a point. In Portland, ME, transit officials said the ads are constitutionally protected political speech because they encouraged residents to vote “yes” on the city’s ballot initiative to legalize recreational use of marijuana.

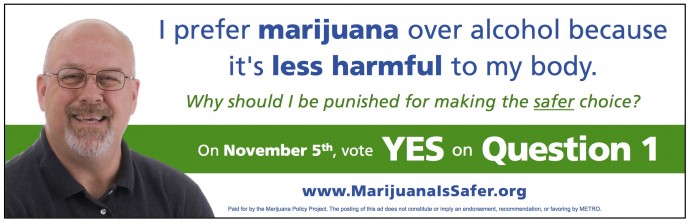

For example, in one ad, a woman’s picture is accompanied with text that says, “I prefer marijuana over alcohol because it’s less toxic, so there’s no hangover.” Another ad featured a man who said he preferred marijuana to alcohol since “it doesn’t make me rowdy or reckless.”

However, opponents argue that pro-legalization ads often contain a message that goes beyond endorsing a ballot measure. Since marijuana is illegal federally, many argue that ads shouldn’t be allowed in places where minors can easily view them.

“What we say and what we do is being watched by the kids in our communities, and they look to us for clues on what’s acceptable and what’s normal and how they should act,” said Jo Morrissey, the project manager for a substance abuse group called 21 Reasons, which encouraged the transit district to drop the ads.

“I don’t know how you can slice it any other way when you say that marijuana is safer than alcohol,” Morrissey said. “I don’t know what they’re trying to say other than their product is better.”

David Boyer is political director for the Marijuana Policy Project’s chapter in Maine, which bought the ads. He said the backlash surprised him, and he defended the ads, saying it’s important that everyone, including kids, knows that marijuana is safer than alcohol.

“When you don’t talk to kids like they have a brain, then they kind of resent you for it and they end up turning everything else out that you do say,” Boyer said. “I think you do the best with them by telling them the truth.”

Mason Tvert, the director of communications for the Marijuana Policy Project, agreed and said, “People are not used to hearing about marijuana via billboards or bus ads, so they tend to spark quite a bit of public interest and dialogue.

“Our goal is to get people thinking and talking to one another about marijuana. We are confident it will lead to greater understanding of the substance and broader support for ending its prohibition.”

But Colorado’s Lenny Frieling, an attorney and prominent marijuana legalization advocate, disagreed, saying, “I don’t think any medicines should be advertised, period, end of story. Whether it’s medical marijuana or something that will give me an erection for eight hours, I find it all inappropriate.

“Ban it all or don’t ban any of it, singling out marijuana is just willful ignorance,” said Frieling, head of Colorado’s chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws.

Talking to Mint Press News, Ken Paulson, president of the First Amendment Center, said “Any ad endorsing the legalization of marijuana would be absolutely protected under the First Amendment,” since it’s a classic example of political advocacy that is protected as freedom of speech.

“Advocacy — calling for change in the law — is always protected under the First Amendment,” Paulson said. Even if the ad doesn’t specifically include a ballot measure, if the context of the ad is trying to build support for the use of marijuana, then the ad is a form of free speech.

Paulson said that municipalities and cities can determine whether to place political ads on buses, but said they cannot discriminate against ideas, meaning that either all political ads can be put on the side of a bus or none can be displayed.

He added that one occasion where a marijuana ad would not be protected under the First Amendment would be if it said marijuana was available on the corner of Third and Vine, since free speech is not a valid defense if a person is committing a crime.

Free speech trumps prohibition

The issue of whether marijuana ads are protected under the Constitution is not unique to the latest election season. In 2004, U.S. District Judge Paul Friedman ruled that a federal law that would have restricted the display of paid, pro-marijuana ads was unconstitutional since it infringed on free speech rights.

In that particular case, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority declined to display legalization ads created by the American Civil Liberties Union along with three other drug-advocacy groups.

The Washington metro transit authorities said they opted to not display the ads since federal law said that any transit authorities who displayed ads that promoted the legalization of medical marijuana, or any other federally prohibited substances, would lose federal funds. Specifically, the group was concerned it would lose $85 million in federal aid.

But the ACLU, along with the three other drug-advocacy groups, filed a lawsuit against the transit station for “unconstitutional restriction,” which Friedman agreed with.

“Just as Congress could not permit advertisements calling for the recall of a sitting mayor or governor while prohibiting advertisements supporting retention, it cannot prohibit advertisements supporting legalization of a controlled substance while permitting those that support tougher drug sentences,” Friedman explained in his ruling.

Talking to the Associated Press in 2004, Graham Boyd, director of the ACLU Drug Policy Litigation Project, said, “The court ruled that Americans have a right to hear the message that marijuana prohibition has been a cruel and expensive failure.”

Although there has yet to be a ruling specifically on the constitutionality of marijuana ads, it’s likely any legal decision will be similar to a 2002 decision by the Supreme Court, which ruled that banning outdoor advertising of tobacco products was a violation of the First Amendment since a 1,000-foot ban on tobacco ads near schools would curtail the information that adults could receive.

Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in his decision that even though tobacco ads are a form of commercial speech, the ads should not be any less protected. Thomas wrote, “when the government seeks to restrict truthful speech in order to suppress the ideas it conveys, strict scrutiny is appropriate, whether or not the speech in question may be characterized as ‘commercial.’”

Free speech experts agreed with the Supreme Court and said, “Under the First Amendment, you cannot restrict speech on the mere possibility that a small amount of children might see the speech.

“The gist of the Supreme Court’s First Amendment jurisprudence in this area is that the government cannot ban advertising directed to adults simply because a small part of advertising will reach children.”