AUSTIN, Texas — New research maps the growing impact of ocean acidification and identifies the regions worst affected, while scientists and world governments are collaborating more and sharing ways to slow or reverse its progress.

Fossil fuels and human industry are releasing increasing amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere where it is absorbed by the oceans as carbonic acid, an invisible but highly destructive substance that’s rapidly changing the chemistry of the earth’s waters and disrupting underwater ecosystems in a process called ocean acidification.

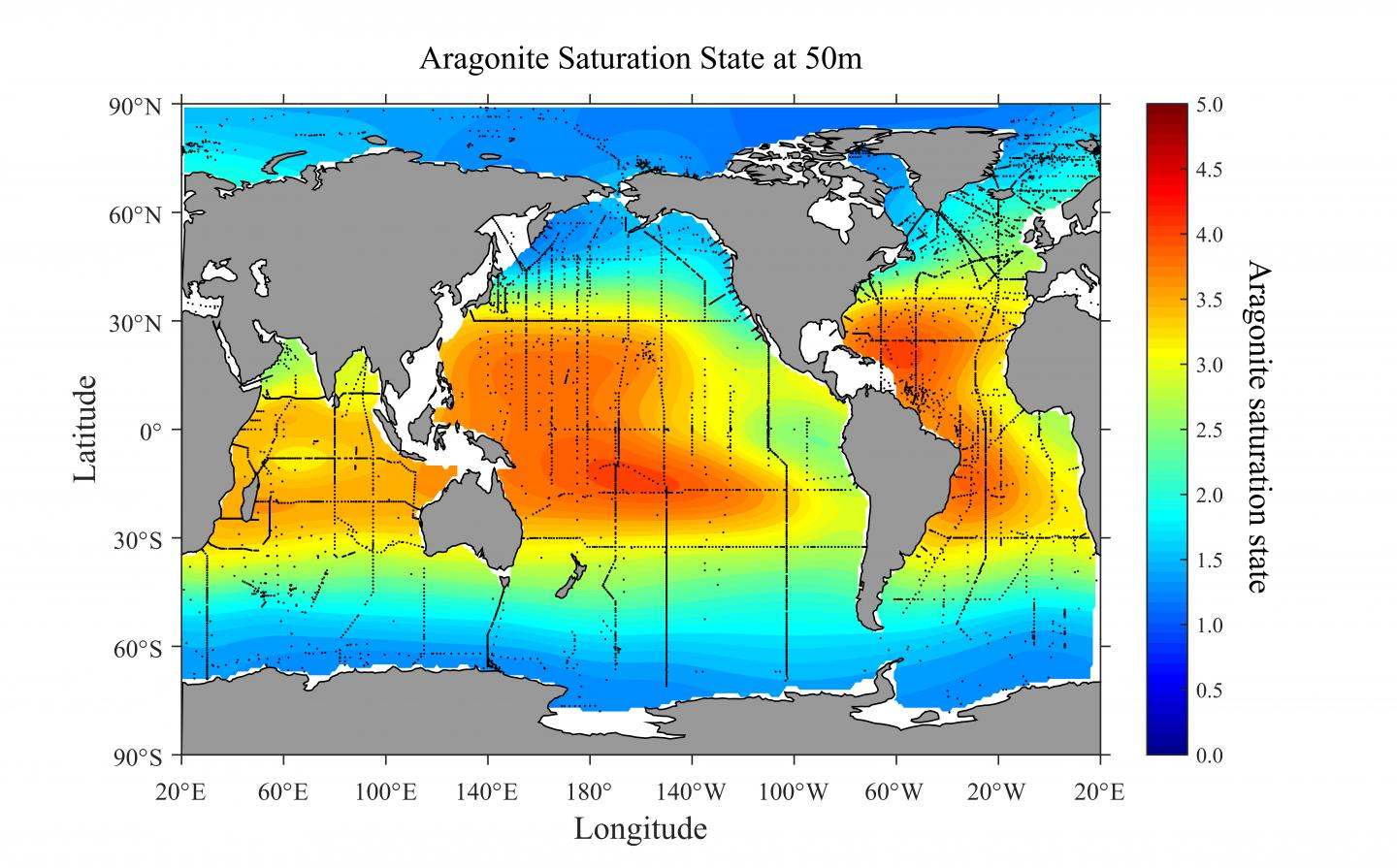

The latest effort at mapping ocean acidification comes from research led by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and published last week in the science journal “Global Biogeochemical Cycles.” The study tracked the saturation levels of the mineral aragonite, which is crucial to the formation of shells in marine species.

According to the NOAA, “The study identifies the Arctic and Antarctic oceans, and the upwelling ocean waters off the west coasts of North America, South America and Africa as regions that are especially vulnerable to ocean acidification.”

Previous research has shown reduced levels of aragonite to be a side effect of ocean acidification that can harm the health of shellfish like oysters and, in extreme cases, cause their populations to plummet. This has already had a negative impact on the fishing industry, especially on the west coast of the United States.

In an editorial for The New York Times published Thursday, Richard W. Spinrad, chief scientist at NOAA, and Ian Boyd, chief scientific adviser to England’s Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, wrote that international cooperation is needed to measure and prevent the worsening of ocean acidification, which they emphasized is just one of several problems threatening the seas:

“The ocean is warming; in many places the oxygen critical to marine life is decreasing; pollution from plastics and other materials is pervasive; and in general we overexploit the resources of the ocean. Each stressor is a problem, but all of them affecting the oceans at one time is cause for great concern. For both the developing and developed world, the implications for food security, economies at all levels, and vital goods and services are immense.”

In addition to the effect on shellfish, Spinrad and Boyd note that ocean acidification can have widespread and unpredictable effects, from making coral clownfish behave in ways that make them vulnerable to predators to causing the rapid growth of toxic species of algae that can threaten fish and other wildlife. One recent study in North Carolina showed crabs have a reduced ability to forage for food in acidic waters.

According to Spinrad and Boyd, the U.S. and U.K. are collaborating with scientists from 30 countries to create the Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network, a new network of sensors that will help more precisely measure the extent of the problem.

In another sign of international collaboration, Dr. Elizabeth Jewett, head of the NOAA’s ocean acidification program, traveled to New Zealand this month to consult with scientists from 13 Pacific island nations.

“We also are predicting impacts on coral reefs’ ecosystems, and that’s very very important for the Pacific islands,” Jewett told a reporter from Radio New Zealand on Oct. 12.

There are some techniques that could mitigate the damage caused by ocean acidification. Studying why some coral appear to be more resilient than others could lead to clues about how to protect crucial reef ecosystems.

Another solution highlighted by Jewett was farming sea grasses. NOAA research, which is detailed in a September report from FIS, a seafood industry news site, suggests that seaweed farms could help combat ocean acidification by removing carbon dioxide from the water.

Watch “Sea Change: The Pacific’s Perilous Turn” from The Seattle Times: