The economic future of this country is now being debated in Washington and it is still unclear as to what the future may hold. There are many who herald the fact that unemployment is under 8 percent — and for those who are recently unemployed it is good news indeed. Yet, we forget, rather easily in fact, that unemployment amongst blacks is over 14 percent.

This is not just a reflection of the times that we live in, but it points to deeper and more abiding problems. A prescription was given to poverty, joblessness and institutional racism in the form of the Kerner Report. What it outlined, sadly, is just as prescient today as was 45 years ago.

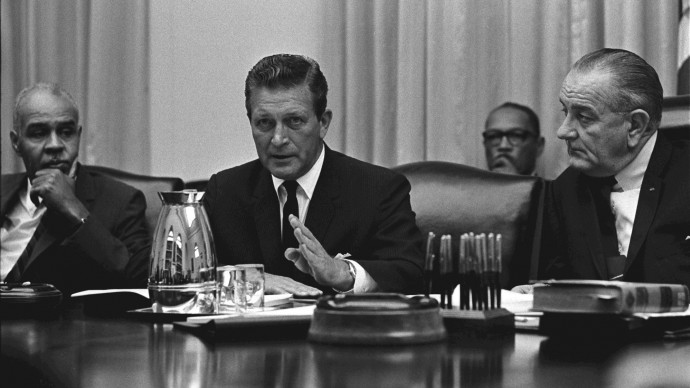

LBJ: Architect of the great society

An enormous deal has been said about the Great Society programs of President Lyndon Johnson — especially as it pertains to black America. And this writer would agree with those who say that opportunities that were not thought possible before 1964 (when Johnson rolled out the first of his Great Society programs), were beginning to be realized.

There were three major pillars of Johnson’s agenda: a war on poverty; addressing racial injustice; and urban renewal and conservation. Nevertheless, these strides were short-lived. Yes, programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, PBS and federal education funding (howbeit with minimized funding) continue with us to this day; the initiatives that were specific to the black community were (and have been) effectively neutralized, diminished or were constantly in peril.

This onslaught is not of recent origin, but began at the genesis of his Great Society. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act (originally authored by President Kennedy) met a filibuster in the Senate by southern senators that lasted 83 days — a sign of opposition to come.

Although Johnson worked tirelessly to make sure that as many pieces of legislation were passed as possible (partly because he was competing against the ghosts of two presidents, FDR and JFK), he was hampered in his efforts by an increasingly unpopular war in Vietnam — which effectively ate away any political capital he may have had. As a result, the progress of these programs was slowed or they were neglected altogether.

The beginnings of the Kerner Commission

Another critical turning point in the Johnson administration was the appointing of the National Commission on Civil Disorders, chaired by Gov. Otto D. Kerner of Illinois (thus the commission came to be called the Kerner Commission).

The Kerner Report was released after seven months of investigation by the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders and took its name from the commission chairman, Illinois Gov. Otto Kerner. President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed the commission on July 28, 1967, while rioting was still underway in Detroit, Mich. The long, hot summers since 1965 had brought riots in the black sections of many major cities, including Los Angeles (1965), Chicago (1966) and Newark (1967). Johnson charged the commission with analyzing the specific triggers for the riots, the deeper causes of the worsening racial climate of the time and potential remedies.

The commission presented its findings in 1968, concluding that urban violence reflected the profound frustration of inner-city blacks and that racism was deeply embedded in American society. The report’s most famous passage warned that the United States was “moving toward two societies, one black; one white — separate and unequal.”

The commission marshaled evidence on an array of problems that fell with particular severity on blacks, including not only overt discrimination but also chronic poverty, high unemployment, poor schools, inadequate housing, lack of access to health care and systematic police bias and brutality (these problems are still with us today).

The report recommended sweeping federal initiatives directed at improving educational and employment opportunities, public services and housing in black urban neighborhoods and called for a “national system of income supplementation.” Dr. King pronounced the report a “physician’s warning of approaching death, with a prescription for life.”

It is necessary that several excerpts from the report be highlighted here: “The summer of 1967 again brought racial disorders to American cities and with them shock, fear and bewilderment to the nation. The worst came during a two-week period in July, first in Newark and then in Detroit. Each set off a chain reaction in neighboring communities.”

The commission’s findings

“On July 28, 1967, the President of the United States established this Commission and directed us to answer three basic questions:

“What happened?

“Why did it happen?

“What can be done to prevent it from happening again?

“To respond to these questions, we have undertaken a broad range of studies and investigations. We have visited the riot cities; we have heard many witnesses; we have sought the counsel of experts across the country. This is our basic conclusion: Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white-separate and unequal.

“Reaction to last summer’s disorders has quickened the movement and deepened the division. Discrimination and segregation have long permeated much of American life; they now threaten the future of every American. This deepening racial division is not inevitable. The movement apart can be reversed. Choice is still possible. Our principal task is to define that choice and to press for a national resolution.

“To pursue our present course will involve the continuing polarization of the American community and, ultimately, the destruction of basic democratic values. The alternative is not blind repression or capitulation to lawlessness. It is the realization of common opportunities for all within a single society. This alternative will require a commitment to national action- compassionate, massive and sustained, backed by the resources of the most powerful and the richest nation on this earth. From every American it will require new attitudes, new understanding, and, above all, new will.

“Segregation and poverty have created in the racial ghetto a destructive environment totally unknown to most white Americans. What white Americans have never fully understood-but what the Negro can never forget-is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.

“It is time now to turn with all the purpose at our command to the major unfinished business of this nation. It is time to adopt strategies for action that will produce quick and visible progress. It is time to make good the promises of American democracy to all citizens-urban and rural, white and black, Spanish-surname, American Indian, and every minority group.”

The report goes on to recommend a number of initiatives based on three principles:

- To mount programs on a scale equal to the dimension of the problems;

- To aim these programs for high impact in the immediate future in order to close the gap between promise and performance;

- To undertake new initiatives and experiments that can change the system of failure and frustration that now dominates the ghetto and weakens our society.

The message unheeded and suppressed

These pronouncements and recommendations were fundamentally ignored. Lyndon Johnson was not a big fan of the conclusions that the Kerner Report had reached — for all the work he had done to ensure the passage of his Great Society legislation, he was still very much beholden to Southern legislators.

Additionally, he believed that the violence and riots that served as the genesis for the creation of the Kerner Commission were the cause of radical groups such as the Black Panther Party and not the white racism that the report pointed to. Finally, as previously stated, Johnson was embroiled and entangled in the Vietnam War that was becoming more and more unpopular; and he was being viewed, increasingly, as unjust.

Nixon, however, had a hand in the suppression of the commission mandates as well. He essentially won the presidency through a conservative white backlash that insured that the Kerner Report’s recommendations would be largely ignored. This conservative backlash could be seen as early as 1968 (after only a little over three years of Johnson’s initiatives) when thousands of Southern Democrats helped former Alabama Gov. George Wallace — and ardent segregationist — carry five states and 13.5 percent of the popular vote. Indeed, Nixon employed what was called the “Southern Strategy” that attracted conservative “Dixiecrats” by appealing to their unhappiness with federal desegregation policies.

Nixon spoke of a “New Federalism,” which would return power in many areas of government to state (which translated into the nefarious “states rights” mantra that has been used to oppress blacks for centuries) and local levels. He cut back on the money for many of Johnson’s Great Society programs, while he turned others over to the states that could decide to continue them or not — a side note: with all of Nixon’s talk concerning a scaled-back central government, it actually increased while he was president.

Conclusion

So without presidential backing; diminished Congressional support; and the loss of the champions and powerful advocates (Bobby Kennedy and MLK) of the goals of the Great Society programs and Kerner Commission’s findings, legislation and programs that were sensitive to the needs of the poor and the disenfranchised, languished under the heat of governmental and societal suppression.

And it is this truth that is missing from the debate concerning the progressive legislation of the 60’s: Programs that were put into place to address over 350 years of injustice against blacks (and other people of color) were given only a little over three years to fully operate and function.

Imagine the potential that would have been realized in this country if, in the words of the Kerner Report, America made “good the promises of American democracy to all citizens-urban and rural, white and black, Spanish-surname, American Indian, and every minority group.”

It appears that the old adage, regretfully, remains true today: Washington is the place where good ideas go to die.