Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, 2nd right first row, poses with Shura members at consultative Shura Council in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia’s new monarch isn’t wasting time. Since assuming the throne Jan. 23, King Salman has elevated some of his closest relatives and sidelined previous power-brokers, tightened decision-making and promised lavish payouts designed to win early goodwill.

Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, 2nd right first row, poses with Shura members at consultative Shura Council in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia’s new monarch isn’t wasting time. Since assuming the throne Jan. 23, King Salman has elevated some of his closest relatives and sidelined previous power-brokers, tightened decision-making and promised lavish payouts designed to win early goodwill.

RIYADH, Saudi Arabia — The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has seen many kings rise and fall over the decades. Yet the death of King Abdullah last month may prompt the unravelling of the last great modern empire, and it will almost certainly lead to a dramatic change in U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East.

While the kingdom’s future policies may not veer far from those put in place by Abdullah, a monarch Western leaders have held up as a reformer and a man of peace, intra-royal relations remain a matter of great concern, according to Sevil Mikayilova, an expert on Middle Eastern and Central Asian affairs and editor in chief of AzerNews, an Azerbaijani media outlet.

“Although the very thorny matter of royal succession was pre-emptively handled by late King Abdullah through the appointment of a crown prince [Prince Salman] and a deputy crown prince [Prince Muqrin], Saudi Arabia’s court is alight with fiercely competitive and opposing ambitions,” Mikayilova told MintPress News.

“Inner tension and political maneuverings are what stand to implode Saudi Arabia and ultimately force Western powers, most predominantly the United States, to reposition themselves in the region through new alliances,” she added.

However, Maziar Behrooz, an associate professor at the History Department of San Francisco State University, argues that the kingdom remains strong and united.

“Although the kingdom of Saudi Arabia is an absolute monarchy, its internal and foreign policy is developed through a consensus among the ruling class, so the death of King Abdullah will not make a major difference,” Behrooz explained to MintPress.

“Saudi policy toward the peace process, Iran or the oil issue will probably not change in a dramatic manner.”

The historic alliance which saw U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt reach out to Abdulaziz ibn Saud, the first king of modern Saudi Arabia, in February 1945 for the sake of U.S. prosperity and geo-strategic positioning, could now be turned on its head. Following two decades under Abdullah’s reign, princes and factions are jockeying for Riyadh, playing sectarian tensions and regional alliances to exert pressure on their political foes — and the U.S. is caught in the crossfire. At the same time, Saudi Arabia’s station as regional superpower has been dwarfed by the rises of Turkey and Iran.

Faced with a series of overlapping social, economic and political crises at home, as well as the ever-increasing threat of radicalism at its borders, Saudi Arabia’s hold on hegemony is wavering.

While Abdullah exerted many efforts toward bringing the region to heed, this sense of control was shattered in 2011. Left blowing in the wind is the very fabric which the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region are woven into.

“[T]hough for a time at least King Abdullah’s policies in the [MENA region] seemed to bear fruits — the kingdom successfully spearheaded counter-revolutions to shore up tyrannical regimes in Egypt, Yemen, Tunisia as well as shielded his own backyard garden by invading and occupying Bahrain — inner political tensions and irresponsible foreign policies now threaten to unravel this house of cards,” Ahmed Mohamed Nasser Ahmed, a Yemeni political analyst and former member of Yemen’s National Issues and Transitional Justice Working Group at the National Dialogue Conference, told MintPress.

Born in the desert of Najd, Saudi Arabia — a kingdom built under the umbrella of imperial Britain, on the back of an alliance forged over two centuries ago between the House of Saud and Mohammed Abdel Wahhab, the founding father of Wahhabism, a violent and acetic branch of Sunni Islam — is eroding.

The very monarchy the British empire helped shape long ago to counter the Ottoman and Persian Empires had been weakened to its very core. In the “Memoirs of Mr. Hempher, The British Spy to the Middle East,” Hempher, a self-proclaimed British spy, explained how at the turn of 18th century imperial Britain sought to exploit Wahhabism as a means to weaken the Ottoman Empire through an agent-country network, like the nascent kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Although the kingdom wouldn’t officially take form until 1932, the House of Saud was long instrumental in remapping the Arabian Peninsula in line with the British agenda.

A crash course in Saudi Kremlinology

“If Washington was rather pleased to hear that King Salman’s first order of business was to elect his full nephew, Prince Mohammed bin Nayef, to deputy crown prince and minister of interior, thus opening the corridors of power to the next generation of royals, U.S. officials have remained blind to the dangerous storm which is brewing in Riyadh over the Sudairi coup,” Ahmed said.

Salman’s rise to power and the nomination of his nephew, Prince Mohammed bin Nayef, laid bare deep national and regional political faultlines.

Though Abdullah’s former crown prince now carries the much coveted title of Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, others appear quite determined to stifle his reign, if not cut it short.

Behind the smiles and the reassuring handshakes, Salman has scrambled to counteract and destroy the ambitions of Muqrin, the leader of what has been dubbed the opposition.

Like his father before him, Mohammed has become a formidable power within the royal family. The son of one of the Sudairi Seven, he carries with him the legacy of one of Al Saud’s most powerful factions.

Salman may have ensured that his direct lineage would rule uncontested through a clever government reshuffle — upon assuming the crown, he issued over 30 decrees back to back, promoting and demoting royals in an unprecedented shake up. Yet it’s just such radical changes which have raised the kingdom’s temperature and led regional powers to choose sides.

Widely believed to be the last capable son of Abdulaziz, as all others, including Salman, are in poor health, Muqrin has markedly different ideas on what direction the kingdom should take — including the highly sensitive issue of power sharing.

Like Salman, Muqrin has sought to assert his clan’s footing in the kingdom. Though this power struggle has remained confined within Saudi borders, developments in the region offer insight into the kingdom’s internal struggles.

“It was difficult, for example, this January to ignore the absence to King Abdullah’s funeral of United Arab Emirates President Khalifa bin Zayed, his deputy Mohammed bin Rashid, and Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed,” Anthony Biswell, an external Yemen consultant with IHS, a global information company, told MintPress.

Openly opposed to Mohammed, UAE royals made sure that Salman would heed their warning. And it’s apparent that the entire region took note of the underlying threat behind the snub.

The Sudairi coup

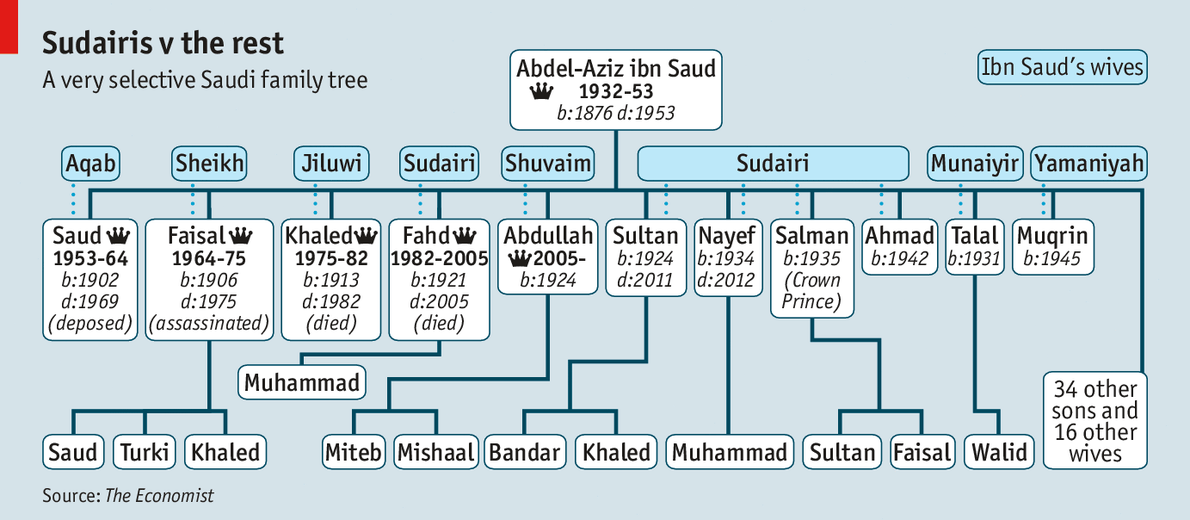

Among Abdulaziz’s 35 sons, the most formidable family group is the Sudairi Seven – named after their mother, Hassa Al Sudairi, who was said to have been Abdulaziz’s favorite wife. By all accounts, these seven have resolutely strived to get to the throne and not let it go. So it came as a great surprise when Abdullah rose through the ranks to be appointed heir to the throne by King Fahd, the first Sudairi monarch, in 1982.

Consequently, Abdullah’s top priority after ascending to the throne in 2005 was to establish an Allegiance Council in April 2006 that included all the factions of Abdulaziz’s family. It was principally designed as to enable the monarch to counter the Sudairi bloc by galvanizing support from marginalized factions.

A keen strategist, Abdullah understood that for the kingdom to avoid falling to infighting, the Sudairi brothers’ ambitions had to be curtailed. Though Abdullah held true to his promise by appointing consecutive Sudairi princes — Sultan, Nayef and Salman — to succeed him, he did so with one key failsafe: He prevented the rise of Mohammed as direct heir to the throne by appointing Muqrin as his deputy crown prince.

Abdullah knew that if Salman were to become king he would certainly name either his full brother Prince Ahmed or Mohammed as crown prince. Thus, Abdullah surprised the court last March by appointing Muqrin, the youngest of Abdulaziz’s sons, as his second nominated heir, stripping Salman of his right to chose his own successor.

In retrospect, Abdullah’s moves may have been dictated by his desire to see his own son, Prince Metab, become Saudi Arabia’s next crown prince under Muqrin’s command and thus secure his own lineage and legacy.

Somewhat of a pariah in Riyadh due to his Yemeni heritage, Muqrin was bound to return Abdullah’s favor by paving the way for his nephew Metab — or so Abdullah envisioned.

“Riyadh’s corridors are, like in any monarchy, full of whispers and manipulations. King Abdullah, like any monarch, intended to secure his bloodline. He did so by positioning Muqrin before the Sudairi line, upsetting Prince Mohammed bin Nayef’s ambitions,” Ahmed, the Yemeni political analyst, said.

Yet Abdullah’s drawn-out illness provided Salman with a golden opportunity. As Abdullah’s hold on power weakened, the then-crown prince devised a Sudairi comeback, exploiting Mohammed’s ties with Western capitals to support his power play.

While Salman has judged it too risky to do away with his imposed crown prince, his decision to dismiss three key figures of Abdullah’s court — Prince Bandar bin Sultan, Khalid al-Tuwaijri and Prince Mutaib bin Abdullah — clearly set a tone.

Days within beginning his reign, Salman dealt a mighty blow to Abdullah’s next of kin, Metab, by not only cutting his kinship dream by appointing a deputy crown prince, but by ripping through his powerbase.

Metab was demoted from his position as the head of the special Royal National Guard and both of his brothers — Prince Mishaal, governor of Mecca, and Prince Turki, governor of Riyadh — were dismissed.

With the Sudairi attempting such a comeback, hundreds of princes have been left feeling more than just a little resentful. Egos and ambitions are set to clash over the crown, and thus, Saudi Arabia’s peaceful transition of power could instead devolve into a violent unravelling.

Playing piggy in the middle

With so many American interests riding on Salman’s ability to quell internal political dissent and silence regional powers’ ambitions to challenge Al Saud’s hegemony in the region, U.S. officials are between a rock and a hard place, especially since building new friendships in the region — with Iran, for example — could equate to gravely upsetting the kingdom.

As Salman will surely look to reassert the House of Saud’s footing in the region by attempting to rally under his flag those powers which have attempted to remove themselves from under Al Saud’s shadow — namely, Yemen, Bahrain and Syria — Riyadh’s policies could prove at odds with U.S. interests.

In Yemen, for example, Washington has invested a great deal of time and effort in engineering a peaceful transition of power in order to safeguard its counter-terror strategy in the Arabian Peninsula. Yet Saudi meddling in Yemeni politics could prove fatal to U.S. interests in the region.

“The Saudi-staged return onto the scene of Yemeni President Hadi following a meeting in Riyadh with Islahi leaders has thrown the country out of its axis at a time when Ansarallah [the Houthis’ political arm] finally set in motion political talks with Yemen’s warring factions under the guise of the United Nations Security Council,” Ali Al Bukhaiti, a former spokesman for the Houthis, told MintPress.

“Riyadh’s interference is jeopardizing Washington’s interests in Yemen, since unrest will benefit al-Qaida and risk throwing more territories at the mercy of terror militants, notwithstanding the fact that Al Saud has resumed throwing money at some of Yemen’s most radicals figureheads to challenge Houthi leadership,” Bukhaiti continued.

In the Levant, where Washington has made some careful overtures vis a vis Iran to unlock a dangerous status quo in Syria toward neutralizing the ever-expanding rise of ISIS, Riyadh’s aggressive funding of radical militias has proven unnerving and counter-productive to U.S. interests.

Yet with petrodollars, military interests and geo-strategic positioning featuring heavily in the equation, Washington can’t just walk away from its longstanding relationship with the House of Saud. It may have to, though. As Felix Imonti, a Canada-based political analyst with Geopolitical Monitor and author of “Violent Justice,” told MintPress, “Washington is realizing that Saudi Arabia is the greatest threat in the region.”