Planned for months, it was decided over dinner.

The raid on a village in rural Yemen reportedly aimed to capture or kill one of the world’s most dangerous terrorists and deliver a stinging blow to al Qaeda in the Arab Peninsula (AQAP), a militant network the US had been trying to dismantle for more than a decade.The collection of small brick houses in Yemen’s dusty central region was home to civilian families as well as militants and was heavily-guarded, meaning a precise, well-practiced operation was paramount.Intense surveillance was carried out for weeks, rehearsals took place in Djibouti, and Navy SEALS awaited the go-ahead from their commander-in-chief. It came just five days after President Donald Trump took office.

But as the elite team descended under the cover of darkness, what could have been the first major victory for the new administration in its renewed mission to defeat radical Islam quickly went dreadfully wrong.

As cover was blown, enemy fire returned and contingency plans failed, tragedy unfolded on all sides.

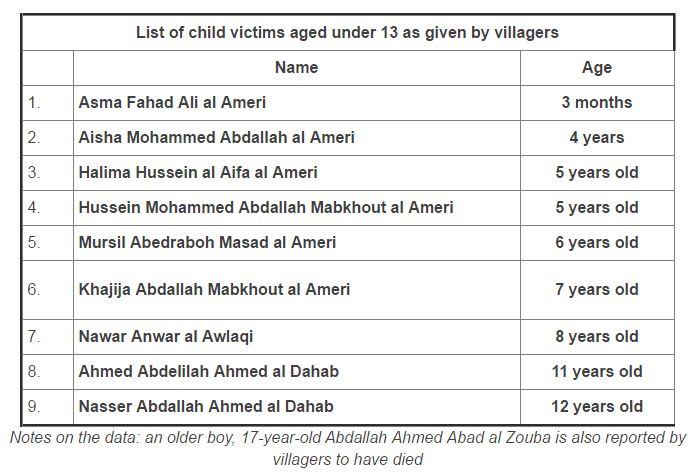

It is already known that 8-year-old Nawar al Awlaki, the daughter of al Qaeda propagandist Anwar al Awlaki was among those who died in the attack. But following a field investigation, the Bureau can today reveal that nine children under the age of 13 were killed and five were wounded in the raid in al Bayda province on January 29.

Details emerged piecemeal last week regarding civilian and military deaths, the disputed value of the targets and deficiencies in planning – some of the information coming from military sources in unprecedented briefings against its own administration. Insiders told CNN and NBC that the ultimate target was AQAP leader Qasim al Raymi. If the soldiers didn’t find him in the village they hoped they would find clues as to his location.

But despite the growing reports of failure – and despite the death of Navy SEAL Chief Petty Officer William Owens and the destruction of a $70 million Osprey aircraft – Trump’s press secretary Sean Spicer has continued to insist that the mission was a “successful operation by all standards.”

Evidence gathered by the Bureau must surely challenge that assessment. A fierce gunfight turned into an intense aerial bombardment, and the outcome “turned out to be as bad as one can imagine it being,” said former US ambassador to Yemen Stephen Seche.

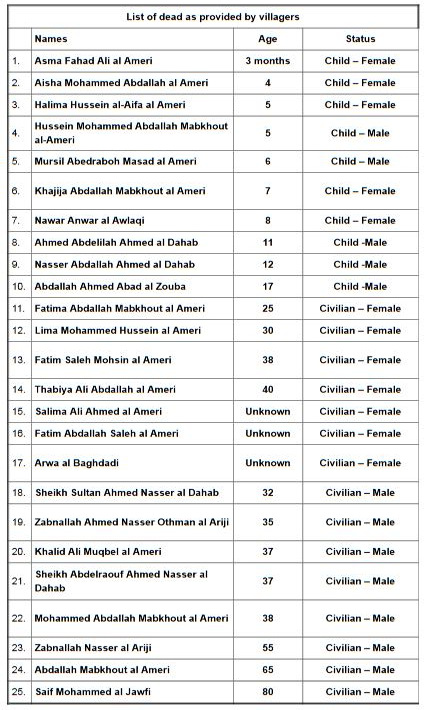

Working with a journalist who visited the targeted village of al Yakla five days after the raid and talked to nine of the survivors, we have collected the names and ages of all 25 civilians killed as reported by those who live there. The Bureau also has photos of the families hit and the homes destroyed as helicopter gunship fire rained down.

AQAP say 14 “of its men” were killed in the clash, including six villagers. The youngest was 17, the oldest 80.

The villagers say 25 civilians died alongside a group of militants, including nine children under the age of 13. They deny that any of the dead villagers were AQAP members. Of the nine young children who died, the smallest was only three months old. Eight women were killed, including one who was heavily pregnant. Seven more women and children were injured.

There is fury at the US for what the villagers say was yet another example of disregard for civilian life in the pursuit of terror.

“It is true they were targeting al Qaeda but why did they have to kill children and women and elderly people?” said Zabnallah Saif al Ameri, who lost nine members of his extended family, five of whom were children. “If such slaughter happened in their country, there would be a lot of shouting about human rights. When our children are killed, they are quiet.”

Villagers described chaos, with people shot as they attempted to flee the gun battle before helicopters opened fire.

“They killed men, children and women and destroyed houses,” said Mohsina Mabkhout al Ameri, who lost her brother, nephew and three of her nephew’s children. “We are normal people and have nothing to do with al Qaeda or [Yemeni rebel movement] the Houthis or anyone. The men came from America, got off the planes and the planes bombed us.”

Civilian deaths can provide ‘recruitment tool’ for terrorists

This is by no means the first US counter-terror operation in Yemen which has killed civilians. Each one has stoked more resentment among the population. Yemeni foreign minister, Abdul Malik al Mekhlafi, said on his official Twitter account that the deaths amounted to “extrajudicial killings.”

A campaign statement by Donald Trump suggests the new leader of the free world may view such civilian casualties as inevitable, or even necessary. “The other thing with the terrorists is you have to take out their families, when you get these terrorists, you have to take out their families,” he said in December. “When they say they don’t care about their lives, you have to take out their families.”

Trump’s statement led to speculation that women and children might be deliberately targeted by the US. But Stephen Seche, who was US ambassador to Yemen from 2007-10, told the Bureau he did not believe America had changed its attitude towards protecting civilians. However “the enormous cost in human life” from this particular raid would damage the legitimacy of American intervention in Yemen, he told the Bureau. “It’s a horrific calculation to have to make and the outcome in this case turned out to be as bad as one can imagine it being.”

Far from delivering a blow to AQAP, the raid may have strengthened it. “Groups like AQAP will contend [this attack] shows Trump is making good on his campaign pledge,” said Letta Tayler, Terrorism and Counterterrorism Researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Even if Trump wasn’t serious, armed extremists are likely to jump on every photo of a Yemeni child killed in a US strike as a recruitment tool.”

“The use of US soldiers, high civilian casualties and disregard for local tribal and political dynamics… plays into AQAP’s narrative of defending Muslims against the West and could increase anti-US sentiment and with it AQAP’s pool of recruits,” said International Crisis Group in a report released three days after the attack.

The alleged target of the raid certainly appeared to think it had helped AQAP’s cause, releasing a message on February 5 mocking the US. “The fool of the White House got slapped,” said al Raymi in an audio recording which military sources said was authentic, reported NBC.

A nightmare unfolds

As Abdallah al Ameri and his neighbour Sheikh Abdallah al Taisi prepared for bed on January 28, they could be forgiven for thinking they had suffered enough bad luck for a lifetime. Both men, subsistence farmers now too old to work their land, had already survived a US drone attack which hit Abdallah’s wedding party in December 2013. They both lost their eldest sons in that attack, which killed 12 people but which the US has never formally acknowledged.

Their home region of al Bayda had been battered since late 2014, as the Yemeni government led by President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi began its slow-motion collapse. In its place, a three-way battle erupted between tribes allied to the government, the Houthi rebel movement and al Qaeda militants. An international coalition led by Saudi Arabia would join the fray the following year.

Yemen’s hinterland, Yakla included, faced Houthi shelling, incursions by AQAP and bombing by US drones – all on top of severe food and fuel shortages wreaked by a Saudi-led blockade. Yemen now stands on the brink of famine.

The day leading up to the strike, rebel Houthis encamped in the nearby Qaifa mountains fired Katyusha rockets at tribal militiamen in Yakla. The militiamen were allied to the internationally-recognised government led by President Hadi. It was a familiar exchange in an ongoing battle for control of the region since the start of the rebellion.

But the ominous sign of things to come was subtler. Sadiq al Jawfi, a member of a local cross-party ceasefire committee which monitors violations at the request of the UN Security Council envoy to Yemen, told the Bureau that mobile phone coverage providing Yakla with its only line to the outside world had been cut. Yemen’s National Security Bureau (NSB), historically allied to former President Ali Abdallah Saleh and now his Houthi allies, had a history of restricting coverage prior to military operations.

It was a moonless night and the calm in Yakla was punctured only by the familiar sound of drones buzzing overhead.

In the middle of the night US special forces flew from the aircraft carrier USS Makin Island in Osprey tilt-rotor aircraft and landed a few kilometres from the village. Things started to go wrong right from the start. One of the Ospreys crash-landed, injuring three of the troops.

“The operation began when the soldiers landed next to the graveyard which lies about 2km away from our town, north of Yakla”, Sheikh Abdelilah Ahmed al Dahab said. The soldiers then proceeded on foot, flanked by military dogs, in the direction of the village. Villagers say there were about 50 soldiers.

An 11-year-old is the first hit

His son Ahmed was the first casualty. According to al Dahab the 11-year-old was woken by the commotion outside and went to see what was going on. “When my son Ahmed saw them, he couldn’t tell that they were soldiers because it was dark,” he said. “He asked them ‘Who are you?’ but the men shot him. He was the first killed. No one thought that marines would descend on our homes to kill us, kill our children and kill our women.”

Tribal leaders Abdelraouf al Dahab and his brother came out to confront the soldiers and were shot dead, committee member Sadiq al Jawfi said. Local sources say they were AQAP members, and press reports released in the initial aftermath of the raid suggested that Abdelraouf and Sultan were among the primary targets of the operation. 80-year-old Saif al Jawfi, who also had al Qaeda connections according to AQAP, came out to see the commotion. He too was killed.

SEAL Team 6 attacked the home of 65-year-old Abdallah Mabkhout al Ameri, surrounding it and opened fire indiscriminately, Abdelilah al Dahab and other witnesses claimed. “When people heard the gunshots and missiles, local men rushed out of their homes to find out what was going on,” he said.

Three witnesses said the commandos shot at everyone who left their homes. In these lawless parts of Yemen every home has a Kalashnikov and the residents reached for their guns “to defend their homes and their honour,” Abdelilah al Dahab said.

The villagers say 38-year-old mother of seven, Fatim Saleh al Ameri was fatally shot by special operators while trying to flee with her two-year-old son Mohammed. “We pulled him out from his mother’s lap. He was covered in her blood,” said 11-year-old Basil Ahmed Abad al Zouba, whose 17-year-old brother was killed.

As the firefight ensued, helicopter gunships appeared and “shot at everything”, including at homes and people fleeing, Sadiq al Jawfi and other witnesses said. Fahad Ali al Ameri woke up to the gunfire. “I was woken up after midnight by the bombing of the helicopters. There were soldiers on the ground shooting at us. They started shooting at us with machine gun fire.” He says a missile fired at his home, killing his three-month-old daughter as she lay asleep in her crib.

The al Ameri family was particularly badly hit. Abdallah, 65, who had survived the attack on his wedding party three years earlier, was killed alongside his 25-year-old daughter Fatima and 38-year-old son Mohammed. Three of Mohammed’s four children also died – Aisha, 4, Khadija, 7, and Hussein, 5. A further nine members of the extended family were killed.

At some stage, al Qaeda militants who had encamped in the nearby Masharif and Sharia mountains descended to engage the US commandos in a fight which would last over two hours. AQAP say 14 of its men died in total: six villagers and eight others.

The eight-year-old daughter of the late radical American preacher Anwar al Awlaqi, who was visiting her uncle Abdelilah al Dahab, was hiding in a room when it was attacked by the gunships, her uncle said. “Some of the gunfire went through the windows and Nawar was injured in her neck,” he said.

The girl would not survive. “We tried to save her but we couldn’t do anything for her,” said Abdelilah al Dahab. “She was injured around 2.30am and bled until she died at around dawn prayers.”

US special operatives made an exit from the village at around the same time, say villagers, but some air attacks continued.

In the days that followed, conflicting narratives emerged. At first, the Department of Defense’s Central Command (Centcom) was bullish, describing the raid as “one in a series of aggressive moves against terrorist planners in Yemen.”

Defense Secretary James Mattis gave a statement honouring the soldier who died. Chief Petty Officer Owens, 36, “gave his full measure for our nation, and in performing his duty, he upheld the noblest standard of military service,” he said.

As details about civilian casualties emerged – most notably that of eight-year-old Nawar al Awlaqi, whose photograph was circulated – the tone was softened. It was “concluded regrettably that civilian non-combatants were likely killed in the midst of a firefight during a raid in Yemen Jan. 29,” said a statement released on February 1. “Casualties may include children.”

Two days later the Pentagon released a video showing a man building bombs which it said had been discovered in the raid. Within hours it was removed from the Pentagon’s website’s after people pointed out the same video had been published online in 2007.

Yemeni government reassesses US relationship

The raid has caused anger in the Yemeni government as well as among civilians. A senior official told Reuters on Wednesday that concerns had been expressed to the US government and in future “there needs to be more coordination with Yemeni authorities before any operation and that there needs to be consideration for our sovereignty.”

The White House, however, continues to insist that the raid was “highly successful.”

“It achieved the purpose it was going to get – save the loss of life that we suffered and the injuries that occurred,” Spicer said in a press briefing on February 7. “The goal of the raid was intelligence-gathering. And that’s what we received, and that’s what we got.”

Centcom did not respond to a request for comment from the Bureau.

US counterterrorism ops in Yemen

The last time US special forces launched a ground operation like this one was in November 2014. It was a rescue mission, trying to spring an American and a South African taken hostage by al Qaeda. Tragically the mission failed and the hostages were killed.

Though US boots have been on the ground in Yemen off and on since 2002, drones and manned jets lead the hunt for AQAP.

More than 162 strikes have left 815 people dead, including 134 civilians (in the last three years of Obama’s presidency civilian deaths in drone attacks dropped considerably). Hundreds of al Qaeda fighters have been reported killed, including a succession of men chosen as the group’s emir.

In 2011, when the Arab Spring reached Yemen and unseated its dictator Ali Abdullah Saleh, al Qaeda took full advantage. It turned from a small terrorist group, focussed on blowing up airliners over the US, to an insurgent group governing a chunk of southern Yemen.

With this transition to insurgency, AQAP became the only group in Yemen to actually profit from the 2011 uprising, according to the recent International Crisis Group report.

In May 2016 US soldiers were deployed to an airbase in the south-western province of Lahj alongside Yemeni troops, coordinating US air strikes and Yemeni ground forces against AQAP.

Together Yemeni soldiers and US air power unseated AQAP from its stronghold but only succeeded in driving the terrorists into the mountains. It has become embedded in the ongoing civil war in Yemen, setting itself up as a Sunni bulwark against the Shia Houthi militias which have occupied the capital since 2014.

Namir Shabibi reported from London and Nasser al Sane from Yakla, Yemen.

Follow Namir Shabibi on Twitter: @nshabibi

Follow Nasser al Sane on Twitter: @nasir2alsana

Additional reporting by Jack Serle and Jessica Purkiss.

Follow Jack Serle on Twitter: @jackserle

This work by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.

This work by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.