On July 6, human rights activist Waleed Abu al-Khair was sentenced to 15 years in prison in the Saudi Specialized Criminal Court. Al-Khair was convicted of making statements to the news media and issuing tweets criticizing human rights abuses in Saudi Arabia. In addition, al-Khair is subject to a 15-year travel ban after his sentence is completed and a fine of 200,000 riyals ($53,327.65 USD).

The state’s case against al-Khair centered around al-Khair’s establishment of and participation in the “Monitor of Human Rights in Saudi Arabia” — a civil rights advocacy group in Saudi Arabia. Al-Khair spoke out internationally against Saudi Arabia’s history of human rights violations and participated in several human rights defense cases — including the case of Samar Badawi, who was accused of disobeying the Saudi male guardianship system.

Saudi Arabia has one of the worst records for human rights among modern nations. Based both on adherence to the Saudi ultra-conservative interpretation of Wahhabi religious laws and fidelity to the royal family, the Saudi legal system has drawn international scorn for its treatment of religious and political minorities, women, critics of their Wahhabi interpretation of Islam, and homosexuals. Only one of the roughly 30 nations that still exact corporal punishment judicially — including the amputation of hands and feet for robbery and flogging for drunkenness — Saudi Arabia has defended its “legal traditions,” which it perceives to have existed since the birth of the Islamic faith. The nation has summarily rejected interference — both internal and external — in its legal system.

Despite claims of privilege in setting its own policies, the Saudi government’s actions have been repeatedly found to be inconsistent with accepted standards of humane treatment. For example, filmed and documented evidence has shown Saudi officials assaulting and abusing workers from developing countries — a group the nation depends on to perform the service jobs Saudis choose not to do, such as garbage collection and shop staffing.

Attacks on the LGBT community, refusal to recognize or permit public Christian worship — including the arrest of 41 people in 2012 for “plotting to celebrate Christmas,” direct attacks and arrests on those who speak against the monarchy, and the suppression of women’s rights — including the extra-legal ban against women driving — have led many to see Saudi Arabia as one of the most repressive regimes currently in operation.

This, however, has not stopped the United States from dealing with the Saudis. According to an April 2013 classified memo that was leaked by National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden and published by The Intercept, the NSA significantly expanded its cooperation with the Saudi Ministry of Interior, even though the U.S. State Department was — at the same time — cataloguing Saudi human rights violations.

“The United States has shown itself willing to challenge countries such as China and Russia on human rights grounds, despite geopolitical situations far in excess of those in Saudi Arabia,” Ali Al-Ahmed, director of the Institute of Gulf Affairs, told MintPress News. “Despite this, the U.S. has refused to not address human rights violations in not only Saudi Arabia, but in Bahrain, for example. As such, this cannot be considered a political issue. It is more a corruption issue; these Arab states have been able to purchase silence and policy positions from the United States.“

Sponsoring human rights violations

The United States’ relationship with Saudi Arabia — despite knowledge of the Saudis’ treatment of those the government deems to be a threat to national security or law and order — have led many, including Al-Ahmed, to believe that the U.S. is — in part — sponsoring the human rights crisis in the nation.

Using American expertise and surveillance technology, the Saudi government has been able to create a surveillance blanket across the whole of the nation so thick that little in regards to anti-Saudi government activism has been able to either enter or exit the nation. A 2013 leaked Snowden document revealed, for example, that 7.8 billion telephone calls were intercepted by the NSA in Saudi Arabia.

“The embassy and consulate people are in touch with the activists in Saudi Arabia and they have up-to-date information — far better than anyone else,” said Sevag Kechichian, a regional researcher with the International Secretariat of Amnesty International, to MintPress about the possibility that the NSA was potentially unaware of the human rights violations committed by the Saudi Ministry of Interior. Kechichian pointed out that the international human rights organizations have been unable to enter Saudi Arabia or establish contact with activists in the country in the last year.

“Everyone is scared to use any kind of social media tool because they fear that the Saudi government are on it, tracking them. The online crackdown has intensified; there is an effort to figure out who said every minute detail, so you have activists and regular people being called in to interrogations, where the interrogators have a print-out of every single tweet, every single comment that they sent. The Saudi expansion of mass surveillance efforts and technology has expanded the state’s repression of free speech and human rights.”

The Saudi-American relationship has led to allegations of cronyism. Prior to Hillary Clinton’s confirmation as secretary of state, the Saudi government gave between $10 million and $25 million to the Clinton Foundation — which also received donations from Norway, Kuwait, Qatar, Brunei, Oman, Italy, Jamaica and the Netherlands.

This is compounded by the 2013 State Department disclosure that Saudi King Abdullah bin Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz gave senior administration members lavish gifts, including half a million dollars in diamond and ruby jewelry for Hillary Clinton and a bare-breasted Liberian female bust for Vice President Joe Biden. As acceptance of gifts over $350 is prohibited for federal government employees, the General Services Administration has indicated that the gifts were either sold to the public or donated.

For some, this has offered corroborating evidence toward understanding some of the United States’ actions in the Middle East.

Conflicted politics

Per the released information paper, the NSA is seeking to expand its relationship with the Saudi government past the standing signals intelligence relationship with the Saudi Ministry of Defense, Radio Reconnaissance Department to the Ministry of the Interior’s Technical Affairs Directorate. This shift is reportedly meant to expand surveillance capability in an attempt to provide terrorist threat warnings against Saudi targets, particularly along the Saudi Arabia-Yemen border.

Since 2004, Yemen has been embroiled in a civil war against the Houthis, a Shiite sect which alleges that the Sunni-controlled Yemeni government has attempted to marginalize and discriminate against them. The Yemeni government counters that the Houthis are trying to establish a Shiite government in Yemen. In 2009, the Yemeni army launched an offensive against the Houthis in Sa’ada province that left hundreds of thousands displaced. The Saudis crossed the border and engaged in an anti-Houthi offensive, leading many Houthanis to speculate that the Saudis are sponsoring Yemen’s attacks against them.

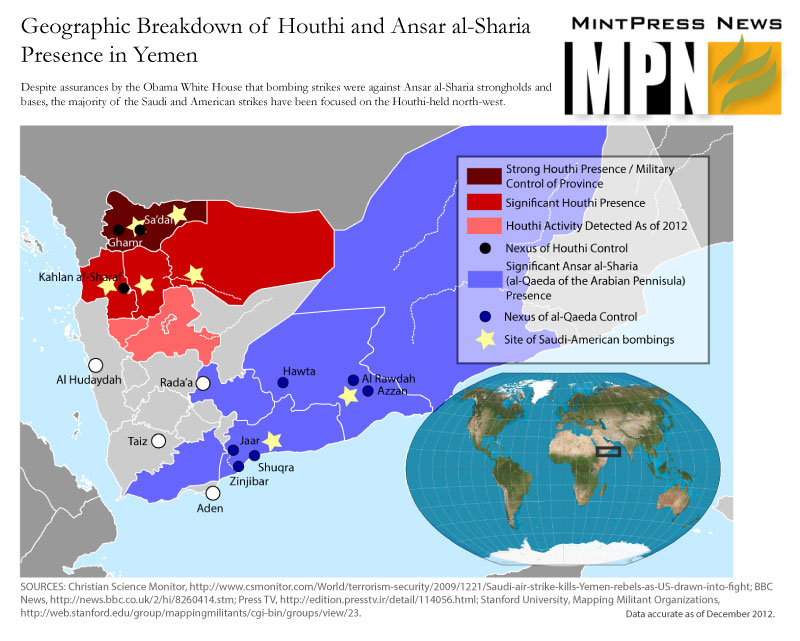

This suspicion was strengthened when the U.S. conducted 28 air raids against Houthi positions in December 2009. The raids, approved by the Obama administration at the request of the Yemeni government against perceived al-Qaida targets, left at least 120 dead and 44 injured. As the al-Qaida forces in Yemen predominantly occupy the southeast corner of the nation, and with the American strikes mostly hitting the northwestern Houthi-held section of the nation, some have speculated that the U.S. may have chosen to do a favor for the Saudis.

Figure 1: Breakdown of Yemen Insurgency

“The U.S. Air Force perpetrated an appalling massacre against citizens in the north of Yemen as it launched air raids on various populated areas, markets, refugee camps and villages along with Saudi warplanes,” said a Houthi leader shortly after the raids.

“The savage crime committed by the U.S. Air Force shows the real face of the United States. It cancels out much touted American claims of human rights protection, promotion of freedoms of citizens as well as democracy.”

Both Yemen and Saudi Arabia have accused the Houthis of receiving support from Iran, another Shiite-controlled region. In 2009, the Yemeni government reported that its navy intercepted an arms-carrying ship heading for the Houthis, and Yemeni state media has alleged that Houthi militants are being trained in a Hezbollah-run camp in Eritrea.

Additionally, it has been alleged that members of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards have met with the Houthis to establish joint operations on the Saudi/Yemen border. This allegation, as well as the fact that the growing number of disenchanted Houthis are adding to the number of Shiite militants appearing in other conflicts throughout the Middle East, has convinced the U.S. to keep a closer eye on the Houthis.

“No one is willing to criticize the United States, except maybe Russia or China or those that are politically opposed to America,” said Kechichian. “In other words, those that may have a credible voice in regards to human rights to criticize the U.S. — such as Europe — would not because the U.S. is a major ally. Most states would rather sacrifice in human rights, ignore what the U.S. is doing and say the minimum in order to save face with America.

“Ultimately, politics trumps human rights.”

Hard questions on perception

U.S. participation in the Saudi police state and its blanket surveillance has been justified by the State Department as coinciding with its “war on terror” narrative. It has, however, become evident through the leaked NSA documents that the U.S. contributed to and is complicit in Saudi Arabia’s human rights violations; U.S. interests in weakening Shiite influence in the region — which the Saudis see as an extension of Iran — have proven compatible with the Saudi interpretation of national security.

According to the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor’s Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 2013 for Saudi Arabia, torture has persisted in the Saudi legal system — even though Saudi law forbids torture and Shariah does not accept confessions obtained under duress.

In 2011, as reported by the State Department, security officials removed Mekhilef bin Daham al-Shammari, a human rights activist being held for speaking against the regime, from his cell at the Damman General Prison and allegedly poured antiseptic cleaning solution down his throat, which resulted in his hospitalization. Al-Shammari would ultimately be released from prison, with the Specialized Criminal Court indicating that it has indefinitely postponed sentencing.

At the time of al-Khair’s sentencing in July, the U.S. State Department came forward with a statement of condemnation against the Saudi government. “We urge the Saudi government to respect international human rights norms, a point we make to them regularly,” said State Department spokesperson Jen Psaki.

Prior to al-Khair’s conviction, Raif Badawi, a liberal blogger, had been sentenced to 10 years, 1,000 lashes and fine of 1 million riyals in May.

In practical terms, the United States’ commitment to the “war on terror” has led the country to make a devil’s deal with a nation accused of domestic terrorism. Per the recently-leaked Snowden document, Saudi Arabia would get from the NSA technical advice for data exploitation and “target development,” as well as help with signal decryption, in exchange for Saudi help in securing access to key areas in the Arabian Gulf. This trade has had the side effect of strengthening the Saudi government’s oppressive surveillance of its own people, leading many to wonder whether the U.S. knowingly enabled human rights violations, and — if the U.S. did act in bad faith — who can hold the country accountable?

However, it may be that the country’s motivations are more straightforward.

“In 2009, the U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia, James Smith, admitted that the U.S. gave the Saudis the munitions, satellite images and GPS locations so that the Saudi air force could target the Houthis,” said Al-Ahmed. “However, news about the United States’ involvement in this situation has not been well-reported. In Saudi Arabia, America is perceived as being part of the human rights violation machinery; it is felt that the U.S. has no regards or consideration for the Saudi people and celebrate a form of institutionalized bigotry in which the human cost for the Saudi people is not considered.”

Al-Ahmed argues that this “blindness” the American government shows to the Saudi people is more a factor of cultural bias than politics.

“The question of why the U.S. feels free to go after Chinese hackers but not Bahraini terrorists that were involved in 9/11 is an important question and goes to the heart of the American-Arab relationship.”