The world is aging so fast that most countries are not prepared to support their swelling numbers of elderly people, according to a global study being issued Tuesday by the United Nations and an elder rights group.

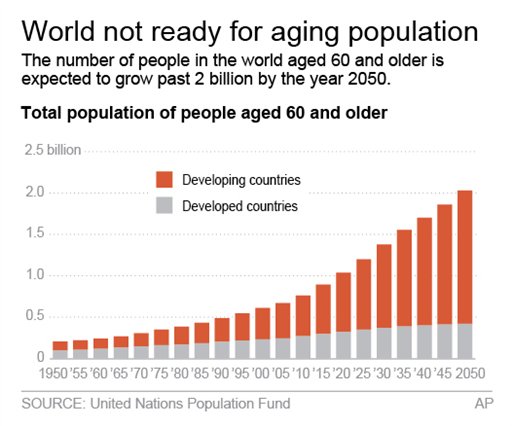

The report ranks the social and economic well-being of elders in 91 countries, with Sweden coming out on top and Afghanistan at the bottom. It reflects what advocates for the old have been warning, with increasing urgency, for years: Nations are simply not working quickly enough to cope with a population graying faster than ever before. By the year 2050, for the first time in history, seniors older than 60 will outnumber children younger than 15.

Truong Tien Thao, who runs a small tea shop on the sidewalk near his home in Hanoi, Vietnam, is 65 and acutely aware that he, like millions of others, is plunging into old age without a safety net. He wishes he could retire, but he and his 61-year-old wife depend on the $50 a month they earn from the shop. And so every day, Thao rises early to open the stall at 6 a.m. and works until 2 p.m., when his wife takes over until closing.

“People at my age should have a rest, but I still have to work to make our ends meet,” he says, while waiting for customers at the shop, which sells green tea, cigarettes and chewing gum. “My wife and I have no pension, no health insurance. I’m scared of thinking of being sick — I don’t know how I can pay for the medical care.”

Thao’s story reflects a key point in the report, which was released early to The Associated Press: Aging is an issue across the world. Perhaps surprisingly, the report shows that the fastest aging countries are developing ones, such as Jordan, Laos, Mongolia, Nicaragua and Vietnam, where the number of older people will more than triple by 2050. All ranked in the bottom half of the index.

The Global AgeWatch Index (www.globalagewatch.org) was created by elder advocacy group HelpAge International and the U.N. Population Fund in part to address a lack of international data on the extent and impact of global aging. The index, released on the U.N.’s International Day of Older Persons, compiles data from the U.N., World Health Organization, World Bank and other global agencies, and analyzes income, health, education, employment and age-friendly environment in each country.

The index was welcomed by elder rights advocates, who have long complained that a lack of data has thwarted their attempts to raise the issue on government agendas.

“Unless you measure something, it doesn’t really exist in the minds of decision-makers,” said John Beard, Director of Ageing and Life Course for the World Health Organization. “One of the challenges for population aging is that we don’t even collect the data, let alone start to analyze it. … For example, we’ve been talking about how people are living longer, but I can’t tell you people are living longer and sicker, or longer in good health.”

The report fits into an increasingly complex picture of aging and what it means to the world. On the one hand, the fact that people are living longer is a testament to advances in health care and nutrition, and advocates emphasize that the elderly should be seen not as a burden but as a resource. On the other, many countries still lack a basic social protection floor that provides income, health care and housing for their senior citizens.

Afghanistan, for example, offers no pension to those not in the government. Life expectancy is 59 years for men and 61 for women, compared to a global average of 68 for men and 72 for women, according to U.N. data.

That leaves Abdul Wasay struggling to survive. At 75, the former cook and blacksmith spends most of his day trying to sell toothbrushes and toothpaste on a busy street corner in Kabul’s main market. The job nets him just $6 a day — barely enough to support his wife. He can only afford to buy meat twice a month; the family relies mainly on potatoes and curried vegetables.

“It’s difficult because my knees are weak and I can’t really stand for a long time,” he says. “But what can I do? It’s even harder in winter, but I can’t afford treatment.”

Although government hospitals are free, Wasay complains that they provide little treatment and hardly any medicine. He wants to stop working in three years, but is not sure his children can support him. He says many older people cannot find work because they are not strong enough to do day labor, and some resort to begging.

“You have to keep working no matter how old you are — no one is rich enough to stop,” he says. “Life is very difficult.”

Many governments have resisted tackling the issue partly because it is viewed as hugely complicated, negative and costly — which is not necessarily true, says Silvia Stefanoni, chief executive of HelpAge International. Japan and Germany, she says, have among the highest proportions of elders in the world, but also boast steady economies.

“There’s no evidence that an aging population is a population that is economically damaged,” she says.

Prosperity in itself does not guarantee protection for the old. The world’s rising economic powers — the so-called BRICS nations of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — rank lower in the index than some poorer countries such as Uruguay and Panama.

However, the report found, wealthy nations are in general better prepared for aging than poorer ones. Sweden, where the pension system is now 100 years old, makes the top of the list because of its social support, education and health coverage, followed by Norway, Germany, the Netherlands and Canada. The United States comes in eighth.

Sweden’s health system earns praise from Marianne Blomberg, an 80-year-old Stockholm resident.

“The health care system, for me, has worked extraordinarily well,” she says. “I suffer from atrial fibrillation and from the minute I call emergency until I am discharged, it is absolutely amazing. I can’t complain about anything — even the food is good.”

Still, even in an elder-friendly country like Sweden, aging is not without its challenges. The Swedish government has suggested people continue working beyond 65, a prospect Blomberg cautiously welcomes but warns should not be a requirement. Blomberg also criticized the nation’s finance minister, Anders Borg, for cutting taxes sharply for working Swedes but only marginally for retirees.

“I go to lectures and museums and the theater and those kinds of things, but I probably have to stop that soon because it gets terribly expensive,” she says. “If you want to be active like me, it is hard. But to sit home and stare at the walls doesn’t cost anything.”