When the threat of terrorism landed on its doorstep in 2001, America grew anxious to devise a way not only to guarantee the safety of its nationals but also to ensure that its founding ideology, the axis which had kept its institutions alive, would be protected against all threats, whether at home or abroad.

When the threat of terrorism landed on its doorstep in 2001, America grew anxious to devise a way not only to guarantee the safety of its nationals but also to ensure that its founding ideology, the axis which had kept its institutions alive, would be protected against all threats, whether at home or abroad.

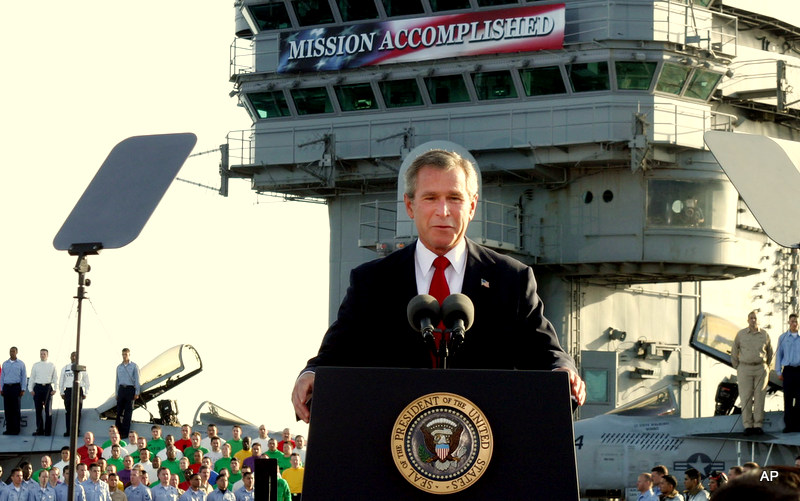

While former President George W. Bush very much asserted the United States as the world’s policing force on all things related to democracy and terror, living under an unwavering policy of exceptionalism, the idea that America stands above the laws of men on virtue alone has been somewhat of a recurring theme over the centuries.

The theory of American exceptionalism was first introduced by Alexis de Tocqueville in the 19th century. The French political thinker and historian often referred to the country as “exceptional” in the course of his writings, setting the tone for a world under the shadow of what former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright deemed the “indispensable nation.”

In an opinion piece published in Foreign Policy in October 2011, Stephen M. Walt argued that America’s overblown and over-valued sense of self is very much embedded in its history, a manifestation of “patriotic chest-thumping” which could not be further removed from reality.

Referring to the United States’ infatuation with its own importance and need to impact and carve the world to its image, Walt wrote, “The only thing wrong with this self-congratulatory portrait of America’s global role is that it is mostly a myth.”

In line with such tradition, Bush unveiled “The Greater Middle East Initiative” in 2004 — a strategy aimed at exporting the American democratic model to the Arab-Islamic world and redefining borders and nations in tune with America’s geopolitical ambitions.

“President Bush quite simply revisited imperialism. He put on paper his intentions to rule over the Arab world, hiding his neo-colonial campaign under the banner of democracy and freedom,” Nasser Sahah, a political analyst based in Yemen, told MintPress News.

If Bush’s “forward strategy of freedom,” was rather ill-received at the time, often branded hypocritical and insincere by his detractors, on the basis that such a policy is inherently democratically self-defeating, it appears today that what the Bush administration envisioned for the greater Middle East in terms of geopolitical, social and even sectarian re-mapping has been hijacked by powers which stand in complete opposition to democratic principles.

Elaborating on what he describes as “America’s undoing of the Middle East,” Sahah said, “President Bush’s cavalier attitude, his failure to acknowledge that democracy cannot be forced upon nations and can never be accomplished by way of foreign military intervention, generated a space for radicals to grow.”

“Today, a decade into what should have enunciated, in America’s mind anyway, the inception of a new way of thinking and being in the greater Middle East has given way instead to grand-scale terror,” he concluded.

Bush and the Greater Middle East Initiative

Before Bush had even unveiled the Greater Middle East Initiative, Sherle Schwenninger, co-director of global economic policy at the New America Foundation, pointed out in a 2003 report that “the essence of U.S. policy over the last three decades has been antithetical to Arab democracy and self-determination.”

“For all that time, U.S. policy in the region has been driven by two at times incompatible goals: the support of Israel and (indirect) control over the world’s oil market,” she wrote.

She also noted “the essential three-part strategy” taken by “every U.S. president since Lyndon Johnson:”

“First, the subsidization of the defense of Israel and the promotion of some kind of peace process between Israel and its neighbors — and more recently between Israel and the Palestinians.

Second, the encouragement of pro-American governments in Egypt and Jordan, removing them from the ranks of hostile frontline states.

And third, the nurturing of a close alliance with the ruling families of the Persian Gulf oil-producing states — especially with the royal family of Saudi Arabia.”

The occupation of Iraq, however, “has only compounded U.S. legitimacy problems,” she wrote. “To most people in the region, it has reinforced their perhaps stereotypical view that the United States is more interested in oil — and maintaining its dominant military position — than it is in the welfare of the Iraqi people.”

Bush’s intervention in the Middle East was felt most acutely in Iraq and the ousting of late-President Saddam Hussein.

It’s known now that there were two main opposing schools of thought at the Pentagon at the time. While neo-conservatives advocated the use of both military force and strong political patronage to bring the region to America’s heel, more liberal-leaning politicians — for example, Les Gelb, president emeritus and board senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, and then-Sen. Joe Biden — proposed breaking up Iraq along sectarian lines, in keeping with socio-religious borders as opposed to the artificial Sykes-Picot Agreement.

Commenting on U.S. policy in Iraq and its ambitions as a power-broker and democratic policing force in the region, Hakim Baha, a retired professor of political science at the University of Baghdad, told MintPress, “Bush’s myopic understanding of Iraq and what forces brought cohesion to the greater region has become a weapon in the hands of groups like ISIL and al-Qaida.”

He added, “ISIL looks poised to follow Vice President Biden’s advice in Iraq. The group understands Iraq’s religious dynamic, it is tapping into it to drive its campaigns, carving zones of influence out of America’s reach.”

What is the Greater Middle East Initiative?

In the wake of 9/11, the Bush administration devised a plan to cut Islamic radicalism off at the roots through the propagation of democratic principles.

“America did not just set out to mold the Middle East to its image, it sought to legitimize its political and military oversight in the same manner an imperial power would over its colonies,” Camille Bellami, an independent researcher based in Beirut, who formerly worked with the Saleh Foundation in Yemen, told MintPress.

“It is this overbearing patronage which has fuelled popular resentment and ultimately fed radicals’ anti-Western narrative,” she added, noting that if Iraq had not been invaded in 2003, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria would never had been able to achieve its current regional takeover.

The Greater Middle East Initiative revolved around three key principles: promoting democracy and good governance; building a knowledge society; and expanding economic opportunities.

As America set out to annihilate Islamic radicalism, the White House identified the Middle East’s isolation from the modern world, high unemployment rates, aggravated lack of economic opportunities, rampant corruption, nepotism and despotism as factors driving terrorism.

“America saw the Middle East and the greater ‘Islamic region’ as an algorithm which required balancing. Rather than attempt to understand the region’s inner dynamics, the U.S. attempted to stamp a pre-defined political, economic and social model onto a society which is profoundly different from its own,” said Baha, the retired professor.

“It has become rather evident that such political mapping has enabled the very forces which the U.S. claimed to want to destroy. Looking at Bush’s initiative one can see that his map of the Greater Middle East resembles almost to a T Daash’s [ISIS’] so-called Islamic Caliphate. Radicals have used Bush’s vision for the region, only to a different end.”

Political analyst Sahah told MintPress that Bush’s military invasion of Iraq triggered a domino effect in the region and prompted the formation of power vacuums. “Radicals exploited America’s political narcissism to expand its hold over key geostrategic axes in the Middle East.”

“What Bush understood as America’s next democratic project, his next grand political scheme in America’s quest for world domination was hijacked by ISIL to bring about the Islamic Caliphate. Where Bush envisioned democracy, ISIL imagined an Islamic empire powerful enough to rival the United States of America,” Sahah continued.

The dissolution of the Greater Middle East

In just over a decade the Greater Middle East has undergone transformations which few, if any, could have anticipated. While the Western world jumped on America’s foreign policy bandwagon to erect protective barriers against terror, it appears that the 2011 Arab Spring opened the floodgates of Islamic radicalism.

In just over a decade the Greater Middle East has undergone transformations which few, if any, could have anticipated. While the Western world jumped on America’s foreign policy bandwagon to erect protective barriers against terror, it appears that the 2011 Arab Spring opened the floodgates of Islamic radicalism.

Speaking from Beirut, Bellami noted, “Washington’s democratic export has but completely ruined the region.”

“Washington’s dual and contradictory narrative, its support of Arab dictatorships while advocating popular political self-determination, has driven a wedge between the people and their respective state officials, pushing thousands to seek an alternative model. Radicals were only too happy to oblige.”

Bellami also stressed that the very reality the Greater Middle East Initiative was meant to prevent, as enunciated by the National Intelligence Council in 2004, actually became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“The rise of the Islamic State as a potent threat to international security cannot be dissociated from U.S. military interventionism,” she explained. “The latter has empowered the former, locking both forces into a vicious cycle which feeds off regional fractures.”

Professor Baha noted that unless there’s a “deep rethinking of the Middle East,” one which would “lean on collaboration and not imposition, one based on mutual trust and partnership rather than embedded in prejudices and fear,” radicalism will only continue to flourish in the region.